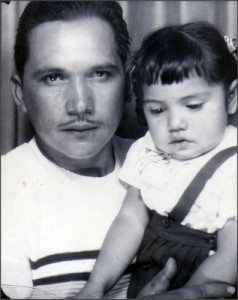

My father was not a tall man, but he always seemed taller than everyone else to me. At 5’7″, he was slim with shiny black hair, brown eyes, and a pencil-thin black mustache. In my memories, he’s wearing blue jeans with rolled up cuffs, a work shirt, and a hat to keep the sun out of his face.

When I was six, he became foreman of the Double Crescent Ranch in Gilroy. We moved into the old ranch house at the back of the property, over a hill and a couple of miles from Burchell Road, the main road through the area. The Double Crescent was a beef cattle ranch, with plenty of room for the cattle to graze and many fields devoted to growing alfalfa.

I loved the ranch with its green hills, fields of lupines and poppies, and craggy oak trees. The ranch house had a wrap-around porch and a large fenced yard with a wide lawn and several trees. There were chickens, a vegetable garden, and a huge barbecue pit. Beyond the front gate was the dirt road leading to the barns and the pastures where the Hereford cattle grazed.

As ranch foreman, my father was responsible for running the ranch and managing the workers. He worked long days outdoors, setting irrigation lines, feeding the cattle, mending fences, and just keeping track of the daily workings of the ranch. We saw little of him during the day, but he was always home for dinner.

The best times were when my father would let me “help” check the irrigation lines. We bounced around in that old Jeep, going up and down the fields. And if I was very good, he would let me “drive” the jeep while he adjusted the irrigation pipes. I’d sit behind the wheel and try to steer the jeep straight, not quite tall enough to reach the gas pedal or brake. I loved the rhythm of the sprinklers as they worked and the smell of damp, green alfalfa.

Other times, I would go with my Dad to pick up the mail from the ranch’s mailbox on Burchell Road. He had replaced the old mailbox with a larger one. The new box had two horseshoes welded together to mimic the ranch’s double crescent brand. The horseshoes and the name of the ranch were mounted at the top of the mailbox. The mailbox was large enough to hold all of the parcels and letters that both our family and the owner received and marked the front entrance of the ranch. When school started, my father would drive me to that same mailbox where I’d wait for the school bus.

I remember my father building a fence around the portion of the ranch that faced Burchell Road. Looking back now, I know that he couldn’t have built it by himself, but I always thought of it as my father’s fence. The fence was painted wood, with three rows of white boards between the white fence posts. None of our neighbors had a fence like it, so it was immediately clear where the ranch’s boundaries were. When I think of the ranch, the fence and the mailbox are the first things that come to mind.

Family was a big thing to my parents, so we always had my aunts, uncles, and cousins over for birthdays, Easter, and Christmas. We had the best yard for the Easter egg hunt, with the lawn, trees, and fences providing lots of places to hide the eggs and cascarones. Family gatherings meant that my father barbecued huge pieces of beef. My father used his special basting sauce to keep the meat moist. It added a buttery flavor to the meat and I’ve never tasted any other barbecued meat that was as good as his. I have a very clear picture in my mind of my father basting the meat, the waves of the heat rising from barbecue, as he laughed at someone’s joke or story.

My father first got sick when I was nine years old. He was admitted to O’Connor Hospital in San Jose and had surgery for stomach cancer. I vividly remember that Easter. Instead of the traditional Easter egg hunt and barbecue with all of the family, my brother and I played with our Easter baskets in the back of our station wagon while we waited for our mother to return from Daddy’s hospital room. To this day, I find it depressing to celebrate Easter.

We had to leave the ranch a few months later; my father could no longer work. He wanted to be close to his family, so we moved to Santa Maria—away from the fields of wildflowers, alfalfa, and grazing cattle to fields of sand, ice plant, and tract houses. Our new home was across the street from Uncle Mike, giving my father daily contact with family. Daddy was able to stay home for while, but eventually had to go back into the hospital.

My last memory of my father was at the hospital. He was in an older, one-story facility, so my mother arranged to have us taken to the window of my father’s room. I had to reach through the bushes to touch my father’s hand through the window screen. I could barely see him, but having that last touch means worlds to me. My father died of cancer when I was 11; he was only 46 years old.

Years later, my new boyfriend (now my husband) wanted to take me on a drive to a special place he knew. We drove to Gilroy and followed Watsonville Road. As we turned onto Burchell Road, I pointed out places I remembered: the orchards where we picked almonds and walnuts; the creek where we waded. My boyfriend was astonished; he thought he was taking me someplace new!

As we passed the old Milne home, I saw it—my father’s fence. It was obviously weathered and had been repaired, replaced in sections, and repainted. But it was still white and still there. As we drove on, we passed the mailbox with its double-crescent horseshoes still at the top.

Both the fence and the mailbox are visible reminders of my father’s work and our life on the ranch. While the fence and the mailbox will eventually be replaced, my memories of them and what they represent will not.

–5/25/2004